The true city, upon which every other city in every shadow is but a pale reflection…

Well, not exactly.

In point of fact, a bit less than half of Shadow could be considered a reflection of Amber. Perhaps a little less than half, if, in fact, Shadow is created by those who travel it, as a reflection of the Power to which they are attuned. Amber, after all, is quite a bit younger than Chaos. And then there’s aberrations like the Forge, Finndo’s attempt at constructing a Pattern, which has, during the course of Finndo’s exile, gathered unto it many shadows of it’s own.

So…

The true city, to which many, many of the multitudinous worlds in the infinity of Shadow owe at least part of their original conception.

Somewhat less impressive, but more accurate.

Of course, things have changed now, since the Tir and Rebma, (which the inhabitants call Caer Beatha) are now true Patterns in their own right, and the Forge has become a full Power as well... those three now scattered on the edges of Shadow, far from Amber, and slowly regaining their own mass of Shadows.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Amber is the most powerful of the Pattern Worlds, and if Shadow were a land war, it would be Amber with the massive advantage.

The actual physical manifestation of Amber is ingrained in the Pattern that lies beneath Mount Kolvir, the Pattern which Dworkin used as the basis for the Anchoring or ‘primal’ Pattern.

(Now, this does of course go against standard beliefs on the subject, which state that Dworkin wholly conceived the Pattern, carved into bare rock on an isolated island that had once been a part of Chaos, which then caused the creation of Amber, such that Amber’s pattern (and the patterns in the Tir and Rebma) is a mere reflection of the Primal. The truth is a bit more complex.)

There were, it seems, several Patterns in existence throughout Shadow: one each for Fire, Earth, Water, and Air… possibly even more that we are, as yet, unaware of, based off elements unknowable to those of our limited nature. What Dworkin did, no less impressive than the fiction that has been popular lore until now, is bind these constructs to one Anchor, a Primal Pattern that forced the original patterns to conform to it’s image and gather towards it until, in a final unnatural balance, the City of Tir na Nog'th hung in the moonlit skies over Amber like a ghost, while Caer Beatha, dubbed 'Rebma' by the inhabitants of Amber as a joke that stuck, lay beneath Amber’s ocean. (The fire pattern having been destroyed during the binding).

Pundits claim Dworkin had read the Lord of the Rings one too many times.

The center of the physical world of Amber is the mountain called Kolvir. Since the world originated from the Amber Pattern, and the Pattern resides in the lower regions of Kolvir's interior, one can understand how a large-scale relief feature, such as a mountain system, erupted around the Pattern.

Mt. Kolvir is a massive, ranging land form of many broad faces and surfaces. Craggy surfaces and winding ledges make only a very few routes accessible even to practiced climbers. The danger of invasion and attack against the palace is curtailed by the ease with which one may perceive climbers approaching along the few routes of easy access.

In general, plate tectonics caused greater interactions in forming continental features in the regions nearest to Mt. Kolvir. That is why the area around Kolvir has such a diversity of features: a mountain range, a valley system, waterways, and forests. These marked variations bear testimony to the violence with which the planet was first formed, thus causing the tendency toward hills and valleys near the point of origin. As one moves away from Kolvir, one notices an inclination to smoother, flatter surfaces. We can see a symmetry in the surface structure that clearly indicates that all the regions range in a circular fashion around the central point of Kolvir.

The most urban area-the city of Amber-surrounds the southern portion of Kolvir, where the city spreads southward, then west and east along the coast to the Harbor District and easy access to the sea. Smaller towns range outward in a circular fashion to both the eastern and western coasts, and inland in the north and northwest. The submerged city of Rebma once lay offshore, southwest of Amber. Out to sea, one finds the island of Cabra, with its lone lighthouse to guide ships to Amber's shore, forty-three miles distant to the southeast. The outer regions, both on land and sea, are bounded by the Golden Circle, which delineates the kingdoms that have commerce with Amber. Some of these kingdoms are in Shadow, but employ open, two-way routes into Amber. Since the Golden Circle refers to boundaries that are not clearly defined, the map of this outer region cannot be accurately drawn.

The palace of Amber, where the Royal Family resides when not traveling in Shadow, is north of the city. Mainly three stories in height, there are several towers that rise higher. The Pattern rests deep in the interior of the mountain, below the palace's ground floor, in the deep recesses of its dungeon. Some say that the Pattern would be found at about midpoint in the mountain.

There are several gardens and ponds around the palace, presenting a serene, idyllic picture of beauty. The countryside around Amber, even in the nether regions, but especially true on Kolvir and its environs, enjoys an unmatched verdancy. Its soil is fertile and rich in minerals; flora are in abundance; and trees and shrubs bear a brilliant lushness, vibrant with life. A visit to the countryside along Mt. Kolvir would be a tourist's delight.

At the highest point of Mt. Kolvir, some six hundred feet above the ground floor of the palace, are three stones, symmetrically arranged. These permanently affixed stones form the first steps of the mystic staircase that once led to the city in the sky, Tir-na Nog'th. Now they are only a reminder of the recent changes.

The most direct route to the palace of Amber is the long, winding eastern stair, a natural formation of ledges in the solid rock. Although the ascent up Kolvir is not difficult on its eastern face, the winding stairway is narrow and a minor misstep could be fatal. Upon reaching the point on a level with the palace, one reaches the top landing of the stairway. It is then a long walk to the Great Arch, the entranceway into Amber. Another way to reach Amber would involve crossing the wide gulf that is the Valley of Gamath to the west, then climbing the western mountain range that connects to Mt. Kolvir. Obviously, this would be a more difficult and cumbersome means of entry into Amber, but an invading army might attempt it in order to secure the secrecy of its movements.

The Main Concourse that stretches through the center of the city of Amber could be reached by descending the rocky southern slope from the palace. Although this path is an easy access to the palace from town, the palace proper is well guarded at that point. As one follows the Concourse, it becomes steeper as one approaches the Harbor area. By taking several side roads in a westerly direction, one would reach the Harbor Road and, at the end of the cove, the pier, where large and small sailing vessels are moored. Although the Main Concourse is well populated, filled with interesting and varied shops, and is well-lighted, the narrower streets of its southernmost portion, near the sea, are often ill-lighted, filthy, and inhabited by some unsavory types of people. It is best not to venture to the Harbor District alone after dark.

At the southeastern foot of Mt. Kolvir, near the shore, is a small chapel dedicated to the unicorn, one of several that have been constructed at sites where she had been sighted in Amber's realm. Along the Mountainside facing the eastern sea are a number of sea caves.

Beyond the city, further to the south and west, is the wide Valley of Garnath. Extending westward from the Valley is the Forest of Arden, which spreads thickly to the west and north. A pleasant little glade can be found in Arden called the Grove of the Unicorn. It has a small, bubbling spring that is fed from a creek flowing northward, skirting Garnath, and originating from the sea in the southern coast.

Cutting eastward, paralleling the southern shoreline, are several lesser, ridged valleys, some cutting into Gamath. Wooded areas also dot these valleys, and seated in one wooded valley is the river Oisen, branching close to the southeast coastal waters.

The realm of Amber ranges far to the west and north, consisting of a terrain of varied texture and sources of production. Near the city, in numerous places around the royal palace, are the palaces of other noble families and the baroque spires of various temples. Far along the eastern coast of Amber, and to the north, are the renowned vineyards of Baron Bayle. Further inland, to the west and scattered widely north and south, are vast tracts of farmland and fenced grasslands for animal husbandry.

Villages in these northern reaches depend largely on agriculture and enjoy a rural, hardworking life. The southerly regions, facing the northern plains above Mt. Kolvir, have the advantage of bordering on both farming communities and mercantile trade lines. These towns employ skilled tradesmen and shopkeepers who have commerce with shipping firms in the city and seaports of the eastern and western coasts. Thus they enjoy an economy that gives the citizenry comfortable yet rustic lives.

The variety and vastness of land in the realm of Amber offers enormous opportunities to citizens who settle here. Although hardships may have to be endured, here as elsewhere, tilling the land is easier than in most places. For the astute businessman, employment is abundant, and skilled tradesmen are in as great a demand in Amber as in any great continent that still has frontiers to tame. Nowadays, immigration is accomplished mainly by invitation, and, on occasion, by accident, but the newcomer has an advantage in knowing the privilege of his position. Few people settle in Amber without the understanding that the world previously known to them was merely a partial reality. They come here aware of their special status, willing to strive for some small success in the real world.

It may be stating the obvious, but the formal written laws governing Amber evolved slowly over the course of centuries. When young Oberon had taken on most of the responsibilities of kingship over a wide and varied populace, a formal code of laws began to develop. This came largely out of necessity, but Oberon comprehended the need for a structured government almost as soon as he entered the task of organizing the people living within the city and its environs.

Initially, Oberon governed over the behavior of the Royal Family under House Law, and it was he, as the reigning monarch, who was the final arbiter in all matters it covered. This was fine, as long as the population outside of the royal household remained small, and, in fact, House Law, in a modified form, is still in effect today. Two factors led to a codifying of a body of laws governing all of Amber: the enormous expansion of people settling in Amber, and the opening up of commercial traffic with the realms of the Golden Circle. Problems dealing with civil, criminal, and property rights cropped up as soon as settlements of people outside of the Royal Palace numbered in the dozens. When the earliest criminal acts of vandalism and thievery were brought to Oberon's attention via messengers of concerned parties among the nobility, he interceded. His first verbal edicts were taken down by scribes and posted in the settlements. These edicts pertained to the maintenance of private rights, establishing compensations for injury or damage to persons or property. The concept of criminal prosecution had not yet become doctrine; offenses were against individuals and were not the concern of the king-they were incidents for private settlement between the concerned parties. "Oberon's Edicts," as they were called, were never drawn into a systematic code. They remain as mere collections of legal rules that are little more than the written records of particular rights of individuals. Nevertheless, they form a common sense basis for a body of custom that was applied to people's rights under the law.

When Oberon took on the full authority of kingship, he became involved in cases in which his written Edicts were insufficient. These cases came largely from commerce with other realms, either in the outer reaches of Amber or in Shadow. Disputes between merchants in Amber and tradesmen of the other realms simply were not covered in the Edicts. After arranging a council meeting with his most trusted counselors and scribes, Oberon took the first steps in drawing up a formal doctrine governing all subjects in his realm. This formal doctrine, after several revisions and additions, has come to be known as the Royal Charter.

In the Royal Charter, Oberon made firm declaration of the extent of his power over his subjects and outlined the beginnings of a judicial system that would be strictly adhered to. It included an oath of loyalty to the Imperial State of Amber that required absolute obedience to the royal monarch and trust in the belief that the interests of the state take precedence over any individual interests. The Charter drafted the formation of Amber as a seigneury that is directly subject to the monarch. As the guardian of justice, the king is sworn to maintain peace during his reign and to "put an end to rapacity and iniquity no matter what the rank of the perpetrator, so that all men may through his justice enjoy peace undisturbed"

Only in matters concerning his person does the king preside over a judicial court in which he is the final judge of a criminal case or civil suit. More often, cases put on trial affecting Amber as a community are held in one of two forms: the baronial court for the nobility, or the seigniorial court for the remaining gentry. To hold the baronial court, the baron of a district in which the legal problem arises acts on behalf of the king. He summons to his court all the literate male adults on register in that district. From these, jurors are selected, their number based on the seriousness of the case before diem, but which may be between fifteen and twenty-five. After the case is presented by both sides, the jurors determine their findings among themselves, knowing that they are acting on behalf of the community and that what they determine will become law. The baron merely presides over the court proceedings and carries out the sentences decreed by vote of the jurors. Cases in which no member of the nobility is involved are held by elected officials of each township, but proceedings are otherwise similar in the seigniorial court as in the baronial court.

Records of all proceedings are sent to the king and kept on file in the Royal Palace. The king is kept up-to-date on important cases that affect legal precedents, and those verdicts which alter or become additions to the Royal Charter are made known publicly. Thus, the ruling monarch shares in, and retains cognizance of, the legal process in his domain. He meets the obligation of defending the law not so much by legislation from above, but by providing the means whereby the community itself determines legal precedent, and by making available the punitive force for carrying out the community's decisions. After all, the right to hold court is a royal right.

Under the stewardship of King Oberon, the common notion formed that law was the possession of the community, and therefore could not be changed at a mere whim, but had to undergo a process of consultation between the king, his advisors, and the district officials. Any major change in the Royal Charter, therefore, is given minute scrutiny and could be revised only after much discussion and compromise between the parties involved. As legal precedents such as tenure rights, inheritance, military service, ward-ship, marriage, and so forth developed, they came to be thought of as a firm body of custom, as rights of citizens that were timeless and unchanging. Once many of these legal precedents had been established, it was generally accepted that any court held within the realm was a court of customary law that bound the king as it did all others.

Where civil problems arise among the merchant class, particularly problems raised by the crafts guilds, means other than the courts may be taken. If the problem involves some labor practice or unfair pricing, for instance, the monarch would usually appoint a council of judges and representatives of the people affected. This council would go over the statutes and recommend revisions in the interest of equity.

Since the Royal Charter places the ruling monarch as the source of justice and the protector of the rights of citizens, it also delineates how the king is to maintain his revenue for the proper governing of the kingdom. In order to retain his authority, the king must be able to supply a reasonable salary for his army, maintain funds to meet his own personal expenses, and preserve a specific allotment of money in his treasury to cover frequent but unexpected contingencies of state. Many of these financial exigencies must come into the royal coffers through taxation. Once a year, every adult citizen, both male and female, must pay a tax on their estimated yearly income, called a chevage. This is paid even by wives who have no regular employment, but who must employ an official auditor for the purpose once a year to determine the amount of chevage she is to pay. When a son or daughter of any citizen wishes to marry outside of the seigneury, the parents must pay a fine called a merchet to the district officer-in-charge. For a son to take up the holding of his deceased parents, he must pay a heriot, which is a kind of inheritance tax, to the district officer. In times of emergency, a local baron, or the king himself, may enforce a tallage to be paid by each family, a contribution that is a fixed payment per family given to the lord of the district to be dispensed only by the king. Although some local barons have tried to abuse the charging of a tallage, community custom often dictated the frequency and amount of this tax. Minor uprisings among the citizenry of a particular district usually had great effect in putting down the demands of an avaricious baron. And no member of the nobility wanted to arouse the displeasure of the Royal Family by showing himself to be prone to angry protests by the people of his township.

A final provision of the Royal Charter is one that is more honored in the breach than in the rule. The Code Duello is one of the oldest customs in the realm, but it had not seen a written form until Oberon drew up the Charter. Trial by combat, in which the contesting parties fought it out or chose champions to fight on their behalf, was simply a formalization of the blood feud. Although implicit in the Code Duello is the belief that if two men fought to settle a problem, right and goodness would ensure a victory for the rightful combatant, it had not been officially sanctioned by any form of religion. However, Oberon knew the practicalities of the matter, and thus set up strict rules to ensure that innocent people would not come to harm as a consequence of two opposing men engaging in trial by combat.

Oberon's directive in the Charter reads: "Although trial by combat is not officially condoned within the borders of this principality, it will be considered an acceptable method of judicial settlement among those whose way of life is ordered by warfare, whose possessions and social rank are ultimately dependent on military prowess, and whose highest ideals are those of bravery, courage, and pride in arms. This will in no way be held as legally justifiable, however, if any persons come to harm as the result of such combat without having the benefit of a background in military field experience as deemed necessary by a court of law. Criminal charges may be brought against a victor on behalf of the injured or deceased party if the above conditions are found to have existed." It must be admitted that this provision was very likely deemed necessary to the mature King Oberon because he recognized the volatile nature of his sons, whose behavior might prove a cause of embarrassment. By allowing for the Code Duello, Oberon at least allowed a channel through which he could prevent the criminal arrest of one or another of his sons after engaging in a personal feud. Some also say that the provision of trial by combat would allow the choice of a rightful heir to the throne to be taken out of the hands of the king, particularly when the right of primogeniture has become so confused by the number and kind of royal marriages. The contentions of various royal factions for the throne can, by the legal process of the Code Duello, be decided, if the need arises, by the survivor in a carefully supervised trial by combat.

In Amber, the Royal Charter is the guiding force that governs proper attitudes of respect of one citizen toward another. Although the Charter may have its limitations, its openness allows for additions and amendments, altered, over the course of time, by the needs of new determinations of trial cases in courts of law. The arrangement of this legal structure of a ruling class of nobility, carefully balanced by the calculated influence of the working class, allows for a well-run society that closely follows the strictures set by the Royal Family. More than merely implied in the writing of the Charter, the continuing authority of the monarch is felt in every disputed case between citizens. Every citizen, whether a noble, merchant, craftsman, industrialist, farmer, or skilled laborer, would refrain from giving offense to any member of the Royal Family. The redoubtable power of the king and his family is recognized by all, but rather than producing an oppressive fear, virtually everyone senses that the monarchy deserves esteem and respect. This is in large part due to the beneficence of Oberon's reign, but also derives from the more-than-rumored belief that the Royal Family is superior to ordinary beings. Some of the citizens who know, who have seen the actual physical manifestations of the power of members of the Royal Family, remind those who remain skeptical, raising doubts in the minds of even the most unbelieving.

The presence of a written document for everyone to see, codifying the law of the land, imbues in the minds of its people the idea that Amber is a state guided by the letter of the law, determined by the will of the community, and sanctioned by the coercive power of superior men acting as the embodiment of righteousness. Those who settle in Amber take pride in the sense of unity voiced in the Royal Charter. There is great satisfaction in this symbol of the underlying belief in the cycle of Amber-Law-Community that is decreed by this royal instrument of justice.

The development of religion in virtually every society has come about because of man's need to explain the forces around him that remain mysterious and uncertain. The formalizing of a religious order through sacred books and the worship of a higher order of beings within a holy construct are important ways in which people attempt to come to an understanding with those mysterious forces. Although this is true for every shadow known to us, it is not necessarily true in Amber. Religion in Amber is a direct outgrowth of the knowledge of higher levels of existence and the understanding that there are superior beings manifest in the world. That is the great difference: The mystery is known to those who live in Amber.

Here is the difficulty that may prove a barrier between those of the true city and those of the shadow worlds. For the shadows, religion is constructed on doubt and incertitude; for Amberites, religion is the giving of a natural reverence for those superior forces that they are cognizant of. Essentially, faith has a different meaning in Amber than in the shadow worlds. In nearly all the shadows, those who practice their religious beliefs fervently do so out of a faith that they are preserving the truth of their precepts without having any objective evidence of that truth. For them, faith, without proof, is everything, and it is enough. In Amber, however, faith comes about from actual observance of unique phenomena. The people possess a natural acceptance of energies that cannot easily be explained in purely rational terms simply because they are manifest in real occurrences around them. But it is just as natural for a citizen in Amber to revere these forces, or objects associated with these forces, because they recognize the preeminence of their influence.

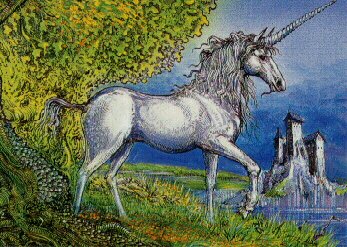

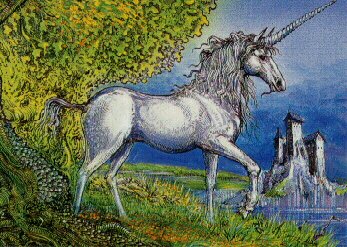

The Way of the Unicorn is the accepted religion in Amber. It has grown into a formalized doctrine of worship from the rumors, myths, and shreds of partial evidence that have been promulgated since the time of Dworkin's rule. Although the Unicorn has become a near-universal symbol of purity and goodness, the Way of the Unicorn does not invest a godlike nature into that remarkable beast that inspires its worship as an omniscient deity. It has been accepted that the Unicorn is a sentient animal endowed with certain mystical powers, and it is an acknowledged part of our history (though perhaps not wholly accurate) that the Unicorn and Dworkin created the universe out of Chaos. However, only a few have actually seen the Unicorn, and many facts about it remain a mystery. It is not known, for instance, if there is but one Unicorn or many. It is not known if the Unicorn spotted by some is immortal-the very being that helped to create the Pattern of Amber-or is a descendant. These questions form a small part of the mystery of the Way that help to feed its worship.

The essence of the Way is in the genuine belief of its worshipers in the sometimes vague but very real power which invests sacred objects and is manifest in important occasions and remarkable personalities. It is a basic, elemental religion that is connected with natural forces, the changing of seasons, fertility, and transcendent potentiality. If this sounds more like primitive nature-worship than the expected political-religious complexities of a faith such as Christianity, it is because the people of the Way are closer to the source of their being, and as such, enjoy a simpler understanding of their place in the cosmic plan.

Those of the Way feel a oneness with the natural energies in Amber, an attraction akin to the attunement of the members of the royal line to the internal logic of Amber itself. This attraction is not strong, and it is probably based largely on faith (or a kind of wish fulfillment), but it creates a sense of reverence for all aspects of nature. True believers have an attitude that the forces of nature sometimes reveal themselves, but are more frequently invisible. These forces have the potential to be beneficial or malevolent, depending on whether one handles them properly or improperly. Unlike people of the more technically oriented shadows, who have been willing to sacrifice the natural beauty of the land so that they could live in a technology that gives temporary comfort, Amberites have a great reverence for the land. Natural objects become the subject of worship, or are used in the giving of blessings or in the process of some ceremony. Such objects as trees, water, stones, mountains, fire, and, of course, certain animals, may be worshipped or become part of some sacred act. In a land where it has been documented that trees have spoken to men, where living water flowing in a brook protects one child in its caress but drowns another who has been tormenting the first child, in such a world nature wields an irresistible influence over belief.

Belief in the spiritual life within all objects of nature is at the core of the Way. In a very real sense, every object contains a spirit, or anima, which brings life to every part of the world, even the very air itself. These anima have personalities that could be offended or flattered. Therefore, it is an important part of the Way of the Unicorn to offer prayer to these anima, to seek to appease them, and to avoid offending them. Before building a house upon a hill, for instance, people of the Way would pray to the hill so that its anima would grant permission. Before cutting a tree, they would pray to the tree spirit, ask its permission, and promise to use every bit of the tree to good purpose. Even in hunting an animal for food, these practitioners would treat the animal with the same respect that they would give a human opponent; the animal is considered a fellow creature with a spirit similar to that of the hunter. The hunters would pray to the spirit of the animal they were hunting. During the hunt only those animals which were needed would be killed. After the hunt all of the animal's body would be used in some way. Nothing is wasted.

Although the royal line has proclaimed the Way of the Unicorn as the official religion of Amber, everyone is aware of the diversity of people who have entered the realm, staying for long periods of time and even settling in its environs. This necessitates an openness to these visitors and settlers, an openness that is amiably embraced by the citizens of the true city. One of the by-products of this openness is the ready acceptance of other religions. Since the time of Oberon's rule, church officials from numerous shadows have been welcomed in grand ceremonies by the king, who has officiated over the commencement of new religious orders and temple sites. The citizens of Amber, having the special knowledge of the origin of the universe, have sometimes been secretly amused by the religious notions of other ecclesiastical orders, but usually restrain themselves from any outward show of derision. In fact, publicly, there is much respect shown to the various religions instated in the realm, and, in return, the Way of the Unicorn is acknowledged as being preeminent and, therefore, having authority over all other religious orders.

The worship of the Unicorn takes place in simple shrines, erected at places where she had been sighted. One such chapel, frequented by the Royal Family, is located on the shore at the southern foot of Mt. Kolvir. Generally, these shrines are small, simple, and numerous. They are not vast halls for the assembling of worshipers, but are meant to be dwellings for the anima. There are regular public rituals at these shrines on holy days, and festivals are planned in the city and outlying villages in celebration. The sites of these chapels are usually not in the center of town, but rather are placed in a quiet grove of trees or on a Mountainside in the country. Simplicity of worship is encouraged, without the encumbrances of pomp and finery.

At each of the sites of these chapels to the unicorn, a small staff of clergy act as caretakers, living in spartan quarters near the shrine. Each chapel is governed by a bishop in charge of the parochial that is, the territorial circumscription of the particular site, roughly corresponding to a town or province. The bishop usually lives in the nearest town, or in the city, so that, at times, he would have to travel some distance by horse cart in order to reach a shrine.

With the passing of centuries, the organization of the religious system of the Way has become rather complex. For each parochial the ecclesiastical bureaucracy is divided into four main departments. These are the camera, which handles finances, the chancery for correspondence, the penitentiary for everything touching on matters of faith, and the rota, the organ for discipline within the order. The bishop officiates over these four departments, but he delegates authority of each area to priests who, in turn, employ a numerous staff of scribes, clerks, and notaries, all of them in the ranks of the clergy. Income for all these people comes from the endowment of the estates of the nobility, set aside for the Way of the Unicorn, from public donations to the shrines, and from the Royal Treasury. Certain employees, not members of the clergy, such as couriers, for instance, are paid a salary through the local officials of the township.

While the bishop is the ecclesiastical governor of his parochial often dealing in affairs of the community that touch upon various matters related to the Way, his control is not absolute. Set in the tradition begun with Oberon, the king of Amber is also its high priest.

Crystallizing the focus of the Way is the holy tome of Dworkin: The Book of the Unicorn. The earliest versions have been said to have been written by Dworkin in his younger days. According to belief, the Unicorn itself had dictated long passages to Dworkin, which were dutifully entered.

Virtually every child receives some schooling during his early years, from about age five to age fifteen or sixteen. There is no system of free public education, but there are many schools throughout the realm of various types and conditions. Frequently, a school is a small structure, usually combined with the living quarters of the schoolmaster and his family. Thus, the schoolmaster is the sole teacher and proprietor, earning his living by taking in a small group of pupils, numbering between twenty-five and thirty. Sometimes, a schoolmaster might be affluent enough in his own right to rent a series of adjoining apartments and hire other teachers who take on classes of pupils, thereby adding to the schoolmaster's wealth. More often, though, a schoolmaster will take on a partner when he can afford to, and together teach a class of pupils each in compartmentalized rooms adjoining the schoolmaster's quarters. Among the nobility, it is common to hire private tutors, who frequently give accelerated courses to their young charges in all the basics so that this phase of their tutelage is usually complete by age eleven. The young heir is then taught the niceties of his class, groomed for the life of a young lord or lady. Besides being literate, knowledgeable about history and philosophy, able to handle practical mathematical problems, he or she must learn the social etiquette of his or her status. For the young of noble birth, the practical is often combined with the social graces, all in the privacy of the manor or palace.

In most cases, the education of children in the middle and lower classes is performed by a single teacher who is responsible for his pupils' entire elementary education. Spelling and the study of Thari are among the first items that the pupils are taught. Language skills become all important during the first couple of years of tutelage, emphasizing grammar, diction, and sentence writing. As they gradually learn to read, they are taught from texts of the classics, many in translation from other shadows. Older children are taught mythological, historical, and geographical allusions by means of these literary texts. Before the pupils complete their early education, the study of literature becomes what is really a form of a "general information" course. Although there may be an emphasis on the "humanities" in the early education of children, other subjects are not neglected. A good teacher is expected to have a broad if not very deep knowledge of such things as etymology, history, mythology, mathematics, physical maintenance, hygiene, music, and religious lore. During the course of their studies, pupils will acquire a liberal knowledge of each of these areas. After getting the fundamentals out of the way, when the student is about age twelve or thirteen, he undergoes vigorous training in the languages and cultures of several shadows. Since the study of three or four specific shadows are required, the pupil may study as many as seven or eight different cultures, obtaining a good working knowledge of dialect and custom, by the time he finishes his elementary education.

By the final year of a child's general education, at about age fourteen, he must come to a decision as to the type of career he would like to enter into. Much time is spent in discussion between the student, teacher, and his parents, evaluating what he has best achieved in his academic skills, and what his natural inclinations tend toward. When he makes his decision, his last year is engaged almost totally in the study of those interests that he has proclaimed. For instance, if he has indicated an interest in becoming a merchant, his year-long studies would place a premium on a knowledge of the legal formulas of contracts, loans, and other financial and commercial documents. If he were to choose other professions, such as the medical, legal, or theological, his training would emphasize areas of study conducive to entrance into those fields of endeavor. If the pupil were interested in becoming a skilled craftsman or tradesman, it might be possible for him to leave his basic schooling before completing his final year in order to apprentice himself to an establishment with an opening, provided the tradesman-in-charge is willing to teach such a pupil.

The vast and varied royal army of Amber is made up of fewer mercenaries and soldiers of fortune than might be imagined. Although there certainly are such rough men who joined for personal gain (hoping to have a good life by pillaging and looting defeated shadows), most of the army consists of youths and career soldiers from the realm.

Enlisting in the army is one clear option that a child, boy or girl, has upon completing their basic education. Many a career man has risen through the ranks in this way. With the possibility of invasion a continual threat to the peace of Amber, there are many opportunities for courageous and skillful men in a number of areas of military service.

Easily the most prestigious area of service is to join the royal guards, who take their billet from the Royal Palace itself. The royal guards consist of a company of men under a captain, making up approximately two hundred men. Once a month about a quarter of the company is rotated into the regular army that patrols the borders and wide expanses between villages. This is done to keep the guards fresh and allow for increased opportunities for advancement. Proven veterans of the guards may remain with the palace if they so desire and have shown themselves especially worthy of such consideration.

The regular army has the sometimes monotonous task of patrolling the realm. This entails long stretches of boredom and practice drills broken only by brief spells of leave to enter the nearest town to drink, gamble, and carouse with members of the opposite sex. Not too infrequently, however, they may engage in battle on short notice. They are the first to be called in the event of an invasion or other such conflict, and they must be at the ready. The regular army is usually broken up into divisions of about five thousand men, arranged to protect a specific region, under a major general. Besides these, there is a small cavalry force for scouting attached to each division made up of four squadrons of about thirty horsemen each.

In addition, several contingency squads are maintained, chiefly taken from the ranks of mercenaries and proven newcomers to the realm, which are assigned as bodyguards, escorts, and containment groups. High officials, noblemen, and ambassadors of Amber usually have members of these contingency squads attached to their personal entourage for protection. Similarly, visiting dignitaries from the shadows are given bodyguards from one of the squads. These squads are also used as armed escorts when travel to shadows, and from one shadow to another, becomes necessary for home and foreign dignitaries who are traveling under Amber's protection. When foreign bases have to be established in other shadows, either temporarily or permanently, a squad (or a large portion of a squad) accompanies the Amberite delegation as a containment group. The squad aids in setting up the base, which includes constructing a camp or arranging living quarters, obtaining supplies, and assuring the general safety of the delegation. Such a containment group may be assigned to the young son of a lord of high influence who plans to attend a university. Under such circumstances, the contingent will remain in that shadow during the entire course of the youth's studies, taking place over several years, during which the members of the squad must provide for all his needs. The contingency group is completely responsible for the welfare of the assigned delegate and is bound by oath to return to Amber with all members of the assigned delegation at completion of the stated task.

Besides the Royal Guard and the regular army is a separate corps that is assigned to deal solely with local and domestic problems. The members of this corps are called vigiles, and they are similar to a military police force. Functioning as a unit that is apart from the rest of the military, they answer only to their internal superiors, and their superiors answer directly to the monarch. The total number of men in the corps is about twelve thousand, but they are seldom retained in such force. They are broken down into six major provinces throughout Amber, with about two thousand armed officers per province. Acting as regional supervisor of each province is a marshal who is directly answerable to the king. Within each province, the vigiles are further divided to serve as a compact, highly visible police force, assigned to a specific township. This usually numbers anywhere from one to three hundred vigiles per township. Far from being troubleshooters or ruffians, the vigiles are trained to deal skillfully with the local citizenry in a calm and courteous manner. Rather than resorting to physical violence, their job involves seeking peaceful means to resolve conflicts. However, although they are given some of the same training as the diplomatic corps, they are chosen for their large physiques and prowess in hand-to-hand combat. In short, if the need arises, they can put down any minor insurrection quickly and expeditiously, with a minimum of fuss.

During peacetime, a full complement of men is not strictly adhered to, so that the numbers of soldiers and military staff employed in the royal guards, the regular army, and the vigiles may be much less. Under such conditions, there is no lack of young men entering the service, since a fair percentage of youths enlist after completing their schooling. Although the pay is small, the attainment of medals, the ceremonial honors amidst parades, and the prestige of promotion make military service an attractive profession.

In time of war or national emergency, it is quite a different story. Every able-bodied man who is employed in a militarily nonessential job is on immediate call to the regular army in the event of war. In lesser emergencies, only young men of draftable age are called to serve. Frequently, these emergency forces are culled from the middle and lower classes, but those of noble birth may also be drafted to serve as officers. Even in peacetime, untested young noblemen are obliged to get some military experience before they are allowed to take on the duties of their ancestral forebears.

A tour of duty in military service lasts four years, except for those men impressed into service during an emergency, in which case their term lasts only for the duration of the alert. It is customary for most young men to serve at least two tours of duty before returning to civilian life. By the time a young man has begun serving his second term, however, he has often become so inured to military life that he is reluctant to leave the service. High premium is given to the glory of awards and rank, and those who enter the service enjoy good fellowship and the security of victuals and shelter. With the sense of order, discipline, and good comradeship, the soldier or officer in the field often retains a sense of patriotism as well. When any member of the Royal Family visits a camp to review troops, the feeling of national pride is dominant among the enlisted men. This can be seen in their performance in drill formation and on the faces of individual young men as they march before a royal dignitary.

Home life and marriage are discouraged, although not altogether forbidden. Certainly, a career man may marry and raise a family, but it must be expected that he will be away from them for long periods of time. Leave time may be accumulated, especially for family visitation, but this cannot exceed three weeks at any one juncture. It is extremely rare that a wife and family will follow an ordinary field soldier during the course of troop movements in the realm, but officers and specially assigned men who are given a fixed placement are likely to live with a wife and children in family quarters.

Both in the regular army and the Royal Guard, drilling goes on constantly. It is more lax with the vigiles, but such routines are dependent upon the frequency of the marshal's tour of inspection as well as the personal quirk of each township's officer-in-charge. Training in arms continues even with veterans well versed in weaponry and tactics, if only to maintain camp discipline and morale. Every man is trained to be a good swimmer, to run, jump, and practice acrobatic feats like the testudo, in which one group of men climbs upon their comrades' heads, so useful in storming walls. Periodically, the men will go on a forced practice march, going at least twenty miles carrying their armor, mess kit, half a bushel of grain, one or two stakes (used as trench markers), a spade, ax, rope, and other tools, amounting to a weight of sixty pounds.

During peacetime, the regular army engages in numerous civilian labors for the benefit of the realm. They may assist in making and repairing the vast network of roads leading outward from the city of Amber to the frontiers. They might work in brick kilns, making bricks for the fortification of the military camps and shelters for visitors and newly arrived settlers. They might be enlisted to help in the construction of new temples, garrisons, or even an amphitheater. While discipline in the army is strict, and labors are seemingly incessant, the civilian work and military training help to instill self-respect and powers of initiative, and these qualities tend to promote personal valor in the heart and mind of the military man.

For the most part, army rations are extremely monotonous, a mere succession of huge portions of coarse bread or of wheat porridge. There are also distributions of salt pork, vegetables, and infrequent poultry. The higher-ranking officers and the company that forms the Royal Guard, however, eat a much greater variety of food, and the royal guards in particular enjoy the varied pleasures of the Royal Palace, certainly on a gastronomic level. Aside from the ordinary drink of milk and water, most of the military men take more heady refreshment from the plentiful supply of Bayle's Piss made available to the army. Frequently, the brew is diluted by the higher-ranking officers, and a small supply of undiluted Bayle's Piss is siphoned off for their private use, before the soldiers are given their small kegs. Although fights and minor drunken incidents do occur, they happen infrequently, kept to a minimum as a result of this practice.

Besides the large armory that is well guarded in the Royal Palace, there are several carefully protected smaller armories kept in the field at fortified encampments. These armories are solidly built structures that remain immobile, heavily guarded, and secret from the civilian populace. Because of the unwieldiness of heavy armaments, and their impracticality, the armories do not stock great machines like catapults. However, a large variety of small arms are maintained in the field: crossbows, cavalry lances, halberds, battle-axes, javelins, longbows (and arrows), short swords and broadswords, and daggers of numerous sizes. Aside from these, the armory of the royal palace also contains several dozen twentieth century rifles from the shadow Earth, with specially designed bullets. These are not in general use.

In battle, the soldier of Amber is a fearsome adversary. Trained ceaselessly in the use of sword and javelin, he is also skilled in defensive tactics. He learns to march, leap, and fight in heavy defensive armor consisting of a stout metallic cuirass of fish-scale plates and a solid helmet of brass. This helmet, having brow- and cheek-pieces for further protection, is so heavy that while marching he is allowed to carry it swung from a strap upon his breast.

The foot soldier's chief defensive weapon, of course, is his shield. Usually the shield is a rectangle of solid leather about four by two and a half feet, rimmed with iron and with handles for carrying on the left arm. A trained infantryman knows how to fend and lunge with his shield with great agility' and by means of the solid metal base in the center' he can strike a tremendous blow. Almost no weapon can penetrate the shield, and, with his cuirass and helmet, a soldier is so well protected against enemy attack that he would seem virtually invincible to an assault by forces of a like number.

When marching into battle, Amber's soldiers are trained to avoid a tight phalanx formation, in which they march wedged together shield to shield, carrying their long spears in front of them. Although such an advance may work well on level ground with the enemy all ahead, it becomes a source of danger to itself because the men cannot easily change position if an attack comes on the flank or rear. In his training, the soldier is taught to stand five feet from his comrades on either side with plenty of room to swing his shield and javelin. Using these methods, a line of infantrymen can easily break up an enemy formation and create havoc in the ranks of almost any foe.

Despite the exception of the diehard mercenary who is mainly interested in enlarging his private hoard of booty, the well-trained military man feels that his whole life is tied up with the army. He is intensely devoted to his corps, its honor, and the honor of his comrades. He has gained a self-confidence that goes beyond simple faith in his physical prowess with his weapons; he has honed his native intelligence, recognizing the power of his mental skills in planning tactics. He is calm in the face of danger because he is prepared, both physically and intellectually, to deal with unknown variables. Such factors-especially those that are unseen-are familiar to the soldier of Amber.

Soldiers of the regular army must routinely deal with "peculiar things slipping through" into Amber from other shadows. Sometimes these "things" must be handled delicately so as not to create a political incident of far-reaching proportions. When a child's pet rattle fell into a heavily guarded region of Amber, and started to consume the grass, flowers, and plant life in the area at a remarkable rate, the soldiers on duty had all they could handle to restrain the living rattle. The situation became more complicated when the small child and his nurse both followed the rattle by the same means into Amber. Fortunately the soldiers were part of a diplomatic corps and, without the aid of any officers of rank, were able to quell the feeding rattle, quiet the screaming child, and calm the querulous nurse. Learning from the nurse that the child was the son and heir of a high prince of a neighboring shadow, the soldiers quietly contacted Lord Julian, disturbing no other official or member of the royal family, and Julian led the wayward trio back to their shadow. Only some years later was the soldiers' deed discovered by King Random, who commended them for their discreet action and good sense.

Similar examples of competence among military personnel run through the whole history of Amber. Some of the greatest sources of inspiration we have for the young man entering army life today come not from tales of heroism on the battlefield, but from stories of individuals who acted out of good sense to find solutions to crises in a distant shadow. Loyalty and ingenuity are integral characteristics for most citizens who choose to actively serve her.

The system of trade in Amber has become a vast and complicated organization. Trade between the shadows and Amber must, perforce, depend upon the direct intervention of the Royal Family. Therefore, the progressive complexity of commerce has been closely interrelated to the business interests of individuals among the Royal Family.

The Golden Circle itself developed as members of royalty delegated their business transactions to those of the noble class who, in turn, assigned advisors to make practical trade arrangements with merchants from other realms, some of which are part way in Shadow. These negotiations became more and more expansive, so that a great network of trade came into existence.

The complexity of trade, with its many subtleties, grew under the reign of Oberon. Even in those early days, Amber's nobles and their agents attracted colonists by offering grants of special privileges in return for draining marshes, clearing forests, laboring in the construction of buildings and bridges, and settling the land. As greater numbers of settlers were invited to live in Amber, a new group of individuals evolved: neither farmers nor laborers, these people were interested in developing enterprises for selling a variety of produce. Beginning locally by buying newly-produced goods from craftsmen at low cost, they sold these products at high profits for themselves. Almost immediately, numbers of these small merchants saw the advantages of a larger trade by working from Amber's several seaports. Those who had the best contacts among the nobility were able to arrange for choice sites in the Harbor District in the city, and then organized sea routes for trade with distant areas of Amber.

Those citizens not born in Amber frequently came from near shadows that allowed for easy access into Amber. Thus, trade lines were more readily opened with these shadows, while the farther shadows remained ignorant of any such avenue of exchange. As a consequence of this ease of commerce with the near shadows, the Treaty of the Golden Circle had been devised. With the frequency of travel, by means of horse-drawn wagon or sailing ship, it gradually became unnecessary for one of royal blood to travel with the expedition. Merchants and seamen became so familiar with the precise location of routes leading to and from Shadow that the journey became second nature to them. On the other hand, containment squads of the regular army were routinely assigned to such expeditions so that the proper trade lines could be strictly enforced. It would not be in Amber's best interests if an opportunistic sea captain decided to forge a new route into a shadow not part of the Golden Circle, simply for his own personal gains. Piracy and plunder would not be tolerated by the royal members, particularly if they were not part of the proposition.

The bartering of goods remained the chief form of exchange for many ages. Amber's metalwork, crafts, lumber, agricultural produce, wine, and uniquely spun cloth were viable commodities for exchange with such needed goods as spices, grains, wool, cotton, wax, sugar, coffee, certain vegetables and fruits, and silk. As commerce grew more complex, and as a glut of many products filled the market, the Amberites turned to a simpler means of exchange: the use of gold and silver coins. The merchants of Amber began by gathering up gold coins they obtained in exchange for goods. This led to complications because coins accepted in one shadow were not accepted in others. In addition, most of the coins had such artistic value that merchants and other citizens who obtained them simply hoarded them away in private collections. In spite of these lapses in circulation, it became increasingly apparent, not only to the general citizenry, but also the king, that a standard form of currency needed to be introduced into the market.

Oberon had smiths prepare silver coins based on shadow denominations, but struck with the likenesses of the royal family and the Unicorn. Thus, the basic unit of Amber's coinage is the "crown"

The mainstay of industry and the social organization of Amber is the individual or family operation. The small shop, selling directly to the consumer over the counter, remains the backbone of society. Shopkeepers in the city and townships open employment for many people in a variety of needed tasks. And, in so doing, the concept of labor has been elevated to remove from it the sense of degradation that has been a part of forced labor in the shadows.

Real worth has been attributed to the numerous occupations that make up the combined strength of a town. Among the citizens of Amber is a pride in the interdependence of the various positions that have played a role in the economic success of the realm. This interdependence is true across the several classes of people: nobles attract merchants by offering convenient facilities and secure routes to and from markets; merchants offer opportunities to shopkeepers to buy and sell at moderate rates; and shopkeepers offer employment to skilled and unskilled workers at the shops and in various capacities centering around the clustered shops of a village or town.

Since the center of any given town revolves around the clustering of shops, other types of craftspeople also tend to aggregate around this center to exhibit their own specialized wares. Among these are musicians and artists, seeking to earn a living by attracting the attention of customers who might not otherwise have sought diversion from more serious business. The success of such artistic endeavors has afforded a remarkable influx of culture, and there has been a great appetite for cultural diversions since the early days of the occasional balladeer wandering through a street fair waving an upturned hat at passersby.

As a consequence of the driving industry and cultural enlightenment of the city and villages of Amber, its citizens have little need to conquer other lands as part of some imperialistic urge. Commercial opportunities with other shadows have enabled its populace to enjoy many luxuries. However, most citizens tend to temper their indulgences with a balanced sense of place in the vast scheme of things. It seems obvious to the enlightened citizen that Amber's financial interests must be gainful, for the fiscal success of Amber is reflected in all the shadows. One need not ponder too long the possibilities if the true city fell into financial ruin: Collapse into a frenetic kind of barbarism at the center would mean the end of civilized virtues at every perimeter.