I’m very excited about the first play session of our new Primetime Adventures game this Wednesday, and while I’m putting a lot of mental effort into it, another game is on my radar, and I really had to share.

There are a few games that I think of as the touchstones in independently published roleplaying ‘story’ games. Sorcerer. Inspectres. Dogs in the Vineyard. Primetime Adventures. The Shadow of Yesterday. The Burning Wheel. My heart wants to add Spirit of the Century to the list, or Don’t Rest Your Head, but while they’re some of my favorite games, they also came along later, and they were built with a somewhat different priority in mind than that first list.

Those who know my gaming habits know that I’ve played or run (or both) most of the games on that list — usually a number of times (usually not as much as I’d have liked) — with good reason. Each one brings something special to the table that either isn’t available elsewhere, or which became an element copied numerous times in other games. They’re seminal, as well as being fun.

The one exception on that list of seminal, inventive games is The Burning Wheel — I’ve never played Burning Wheel.

Now, that isn’t to say I didn’t OWN the game — I had the very first edition of the game, hand-numbered, in pencil, with a little thank-you note from Luke Crane.

But play it? No, I did not.

Don’t get me wrong; it’s a good game – many many people will say a great game – but it’s very very crunchy.

And I don’t mean it’s “Crunchy for a Story Game,” the way Agon is; I mean it makes games like DnD, Warhammer, and GURPS look like diceless freeform.

Those other games reward players with better ‘performance’ once the players have achieved a degree of system familiarity. Burning Wheel goes a bit other other direction: it punishes the absence of system familiarity – it is through system knowledge that one achieves nominal – rather than exceptional – performance from one’s character.

At the time that I got Burning Wheel, I was already doing a very long-running DnD game, and frankly I didn’t *want* to run another crunchy, high-GM-prep system; I just didn’t feel as though people wanted to dive in and learn a whole new system with that much detail. Hell, *I* didn’t; the game sat on my shelves for several years – skimmed, but unread. If it came up in conversation, I mentioned that I really wanted to play the game with some people that understood it before I tried to run it myself. In the meantime, I ran other games — with DnD handling our/my need for crunchy tactical games, our indie gaming was taken up with other things — with limited gaming time and ever-shrinking schedules, the folks I play with are just more likely to choose games with a lower level of required investment than BW.

But I never quite abandoned my interest in the game. Everything I heard about the game sounded – to my tactical-loving side – quite cool, and the raves and praise heaped on the “Story” elements of the game (character Beliefs, Instincts, Traits, and Goals) were just as effusive. When the Revised version of the game came out, I picked it up; when Burning Empires came out, I read and re-read information on the game and its setting. But it was still a game that took too much time to learn, too much time to prep.

Then came Mouse Guard.

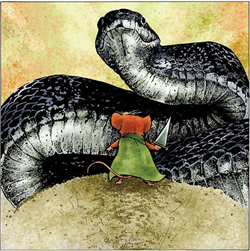

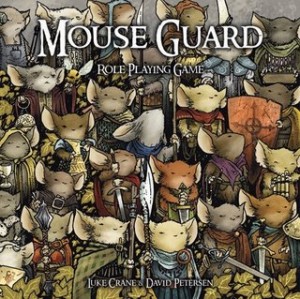

Mouse Guard is a roleplaying game where players assume the role of the titular Guard from the comic books by David Petersen: bipedal, intelligent mice who protect their communities from a variety of threats in a semi-medieval setting. There is no magic in the setting, nor are there any humans; the threats to those precarious communities are the seasons, the weather, the wild animals, and (sadly) the very mice the Guard are sworn to protect. Their goal is simple: to keep the roads open within the Territories – to keep from becoming prisoners in their own cities – mice in gilded cages, if you like.

To me, the idea that the creators behind Mouse Guard (who were also RP gamers of a more classic sort) wanted to have an RPG for their product didn’t surprise me – nor did the fact that they wanted a more story-driven game. What surprised me was that they were going to get the Burning Wheel crew to do the game. What surprised me the most was what I started to hear about the Mouse Guard RPG:

- A streamlined version of the game. The sparest, most elegant iteration of the rules, to date.

- Accessible to new players – not just new-to-BW, but new to Roleplaying.

- Still a true and excellent representation of the Good Things That Are Burning Wheel.

- Strong player-centered focus of play that’s built directly into the rules in numerous ways.

- Lots of situation-generating hooks built right into the characters, making running the game easy.

- Several procedural innovations that make elements of play that are problematic in other games (high crunch = high prep time) very fast and easy.

- There are already a number of ‘hacks’ to port the game to settings that I find very interesting. (Such as “Realm Guard”, which involves playing Dunedain in the 4th Age of Middle Earth. Mmmm good.)

Also, it didn’t hurt that the book itself — 8″x8″, hardbound, 300+ pages, but with a ruleset that can be completely summarized on the backside of the official character sheet, and thus chock full of setting material, advice, and artwork rather than charts — is f’in gorgeous.

So I got it.

I read it. Cover to cover, like a good book. I annoyed Kate by reading sections out loud, explaining rules she didn’t care about, and recounting examples from the source material she’d never read. Hell, I’m still doing it.

Here are some of my thoughts.

Rewards

In short:

- The player defines the character via their Beliefs, Goals, Instincts, and Traits, and it is ONLY through bringing those elements to light during roleplay, in the game, that you are rewarded with Fate and Persona points (which probably do pretty much what you expect).

- Skills improve through active use. Period. Through play. Period.

The Mechanics of Success and Failure

Basic tests in Mouse Guard are simple RPG fare: either unopposed or “versus” checks – in either case, the player needs X number of successes to achieve Unmitigated success. Your skills are numerically rated (usually from 1 to 6), and when tested, you roll a number of d6s equal to the skill rating, count those rolling 4 or higher as successes and discarding the “cowards” that came up 3 or less. If you’ve played Shadowrun or Vampire, you’ll recognize this.

The innovation here is that there is no failure result in the game. What’s that? A crunchy-tactical game where you can’t lose?

Kinda. If you fail to get success outright, success is achieved at the cost of “Conditions” or a “Twist.” With conditions, you win, but you acquire (or more) conditions, such as Tired, Sick, Hungry, Angry, Injured, and so forth.

So you can save your wounded companion, even if you blew the roll, but now you’re Tired.

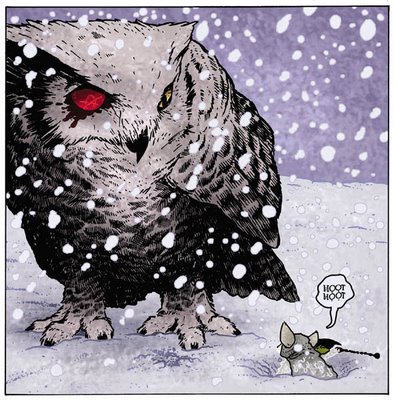

You can escape from the Owl, but you’re Injured… and Hungry… and Tired. Ouch.

Twists work similarly, but instead of taking a condition, your conflict is interrupted by (or leads to) a twist that takes the story in a new direction… and which very likely leads to ANOTHER conflict.

In other words, that bedrock concept of Indie Gaming GMing – “Failure should make things more interesting.” – is hardwired into the game.

Scripting

Scripting is a core concept of extended Burning Wheel conflicts — the “big” conflicts in BW use this kind of conflict, where opposing sides pick a short series of actions without knowing what the other side is going to do — potentially leaving themselves wide open at the worst possible moment, or tactically outguessing the other side at the perfect time.

I love the concept of scripting – it has that kind of immersive realism I sometimes enjoy – but in practice, I know the BW implementation leaves some people cold.

In Mouse Guard, the scripting is a far more streamlined version of the basic BW scripting… simpler, but with powerful choices — perhaps the best implementationof the mechanic. Far from being just a guessing game, you have to weigh which actions your character is good at, which your partners are good at, which your “weapons” are helpful for (scripting works in any kind of conflict, from weapons to survival to chases to oration debates), compare each of them to the actions the opponent might do taking into account what he and his weapons are good at… and then realize your opponent is doing all that too, at which point it becomes very much like a strategic board game mechanic, in terms of the mental gymnastics required to use limited information to outwit the other guy.

And, like the basic skill tests, Failure and Success has many many shades — it’s only by utterly defeating your opponent without letting them get a paw on you that you get exactly what you wanted, exactly how you wanted it.

Teamwork

Teamwork is vital. That’s one of the fundamentals of this game. You are little mice in a great big world, and quite frankly you will be ultimately unable to complete your missions if you don’t work together – eventually, even with the skill system having “outs” for failed rolls, you’ll hit a Full Conflict with scripting that simply blows you away, with no way out but death. The prey are bigger than you (hell, the herbivores are bigger than you, and they’re eating all the food!) the seasons are bigger than you, the weather is bigger than you… you need to help each other.

“Call it what you like, but I’m still failing”

Now yes: failure isn’t “failure” in Mouse Guard, but it stings to play a game and lose the first conflict – maybe the first several – but the way the game is set up, all that means is that a new, unexpected situation crops up. (And in other way, reminiscent of With Great Power, such struggles feed you the resources you need to Kick Ass later.)

There are a lot of games out there that are basically mission completion games. The point of those games is to use your resources well in order to successfully complete a mission. In those games failing the mission is failing; it isn’t game-destroying, but it is a failure. You had a chance to step on up, and you didn’t step, as it were.

Mouse Guard looks a lot like a mission-completion games. Mouse Guard feels a lot like a mission-completion game. But I don’t think Mouse Guard actually is a mission-completion game.

Mouse Guard is a game where you tell a story about heroes who go on a mission (little heroes, but still). That’s a close thing, but its also a sharp and important divide.

One of the most excellent things about that difference is that it might teach everyone at the table to let go a little bit and try something heroic rather than spend ten minutes figuring out a safer plan.

Conclusion

I don’t care if it’s mice (though I like the other settings people are porting the system into) — the simple fact of the matter is that I think this is one of the best tactical, crunchy, story-driven games out there — maybe the only one that’s all three.

I can’t wait to play.

I was a big fan of the first volume of Mouse Guard, published by Archaia Studios Press, which also publishes the Artesia series that spawned an intriguing RPG, Artesia: The Known World. I discovered it a few years ago, at the tail-end of my second go-round with D&D and never got to play it, but the rulebook is a beautiful and fascinating read. I think I’ll be adding the Mouse Guard RPG to my collection. Thanks for the heads-up!

I want to play.

Money graf here: “One of the most excellent things about that difference is that it might teach everyone at the table to let go a little bit and try something heroic rather than spend ten minutes figuring out a safer plan.”

That would be worth the price of admission right there. Not being thoughtless or careless or rash — unless that is, in fact, your character’s traits. But taking chances, come what may.

Creatures who deliberate too much don’t actually survive well (cf. Hamlet).

Yeah, I want to play. I think Margie does, too. And Kitten, for that matter.

Kate has asked me a number of really cogent and valid questions about the game, because (unlike me) she’s played Burning Wheel at least once in the past, and didn’t the massive number of fiddly bits. I think she’s gotten a positive impression of the MG version of the rules.

One of her questions had to do with scripting as a group:

If you have, say, three mice in a group and you’re going up against an opponent in a major conflict, your three scripted actions for the first ’round’ are distributed evenly among the three characters. You don’t just Script “Defend, attack, maneuver”, you also have to say WHO is doing which action. Who has the best stat for said action? Who (likewise) has a tool that will help them with that kind of action, or a pile of Persona points they can use to bring in their Nature? And will the opponent guess all that?

For my money, Team Conflicts really feel like you’re all working together to take down a foe in a way I’ve NEVER seen in another game.

Her question was: “well, if there’s a character with good “Fighting” and a sword, isn’t he ALWAYS going to be the guy doing the Attack action? Is that fun for everyone?” My response, and I think it’s true, is that it’s good to establish that guy as the “Attack” guy… and then have him do something unexpected. A strong attack is, perhaps, weaker than a less-powerful attack that your opponent didn’t see coming.

Not a great ‘reply’ on my part, but something I hadn’t thought to mention in the original post.

That makes sense. Plus being the “attack guy” doesn’t mean always just launching into things full-tilt (or, if it does, that can have its own consequences). Plus, not all conflicts are Fighting kind of things.

One of the things that really made the LintKing grit his teeth in _Burning Empires_ (although to a lesser extent in _Burning Wheel_) was the lack of choice in character generation; there is very little in the “open-ended” opportunity to break out of the set character concepts. Does _Mouse Guard_ allow for a lot of character fiddly?

That’s a common complaint with most “life-path” styled chargen systems — the upside is that the lifepaths really paint a picture of the way the world is; the downside is that it’s hard to break the mold. It’s ESPECIALLY true of Burning Empires, as the life paths reflect a specific Intellectual Property.

Mouseguard doesn’t make use of Lifepaths. Basically, this is because all the players are Guardmice — that’s your ‘life path’, such as it is. This means that all your character differentiation comes from selecting skills, traits, friends, enemies, family, home town, and things of that nature.

So: everyone is a guardmouse — within THAT constraint, you can pretty much do whatever. (Within the limits of the setting, which doesn’t have, for instance, magic… though you can do some pretty amazing things in-game with Scientist and Weather Watcher.)

I would say that the ability to realize a personal concept is very well realized in the game, provided you don’t have someone who’s bound and determined to play something like… I dunno… a steampunk reanimator of dead flesh.

Hey, how are the comeeks?

I fail at deciphering; what’s a comeek?

I think she means “comic.”

For my taste, a little dark and terse. Gorgeously rendered, and the backstory is all lovely, but I had a difficult time getting into the actual story being told.

Not what I would call a “kid” comic, as one might expect re talking mice. Mature kids might enjoy it, and there’s nothing objectionable, but …

Ahh.

It’s a bit like Tale of Despereaux — not as fun and whimsical as you’d expect… more serious. And ToD is has a little more Fun than MG.

Mouse Guard… if Fafrd and the Grey Mouser were mice… and guardians of the peace? It’s a bit that tone. Or the Deryni books.

Weird comparisons, I suppose.